In 2009, Bolivia was transformed from a republic into a Plurinational State with a supposed commitment to protecting Indigenous territories and Pachamama. Yet the Plurinational State also reclaimed an active role in managing and exploiting the nation's subterranean resources - a role that comes into frequent conflict with Indigenous territorial autonomy.

In this context, this project examines how the Bolivian subsoil was produced and is maintained as a national space, even as the surface can be privatized or collectively owned. Focusing on the roles of geological sciences, global commodities markets, and embodied subterranean labor, it provides a "material history" of Bolivia's resource nationalism, which is grounded in the subterranean and exists in spatial tension with the soil-bound politics of plurinationalism.

Research for this project was undertaken between 2012 and 2020. The monograph - Subterranean Matters: Cooperative Mining and Resource Nationalism in Plurinational Bolivia - will be available from Duke University Press in March 2024.

In this context, this project examines how the Bolivian subsoil was produced and is maintained as a national space, even as the surface can be privatized or collectively owned. Focusing on the roles of geological sciences, global commodities markets, and embodied subterranean labor, it provides a "material history" of Bolivia's resource nationalism, which is grounded in the subterranean and exists in spatial tension with the soil-bound politics of plurinationalism.

Research for this project was undertaken between 2012 and 2020. The monograph - Subterranean Matters: Cooperative Mining and Resource Nationalism in Plurinational Bolivia - will be available from Duke University Press in March 2024.

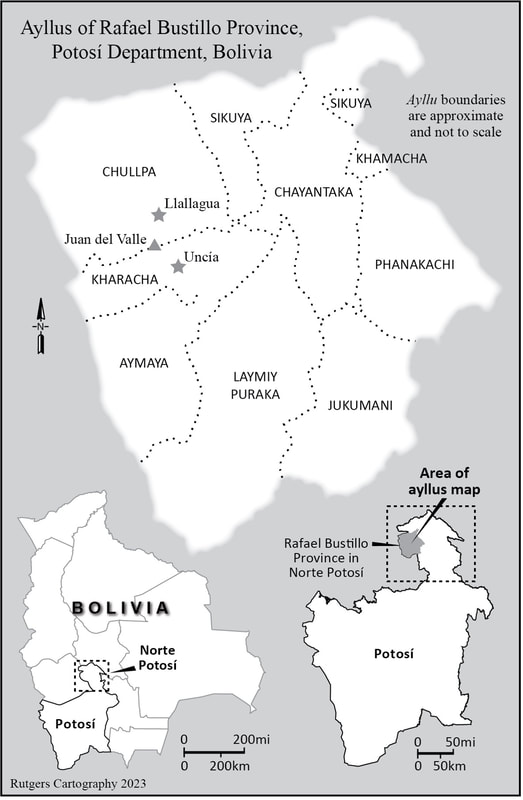

Methodologically, this project draws on ethnographic work with mining cooperatives in the towns of Llallagua and Uncía, in the region of Northern Potosí. Working independently from the state or private companies, mining cooperatives have been rendered thieves of national resources, or thieves of patria (country). Yet with the founding of the Plurinational State, they have moved into positions of political power, thus giving shape to Bolivia's political economy from within. In the book and in several publications, I examine these dual processes with the ultimate goal of understanding how resource nationalism is reproduced both above- and below-ground. To understand these dynamics, I spent a lot of time underground with cooperative miners. I also shared time with them in meetings, community gatherings, protests, workplaces, and government offices.

In addition to the ethnographic work, I also did archival research (ranging from official state documentation to haphazard basement collections) and I conducted interviews with scientists, activists, community leaders, politicians, and other researchers. But the ethnographic evidence forms the core of the project.

In addition to the ethnographic work, I also did archival research (ranging from official state documentation to haphazard basement collections) and I conducted interviews with scientists, activists, community leaders, politicians, and other researchers. But the ethnographic evidence forms the core of the project.

Conceptually, this project advances an analytic I call "material history," which works across Marxian historial materialism and feminist new materialities. It proposes that the material objects and "natural" resources that are drawn into economic processes have histories that both precede and inform capitalist relations. Applying this analytic, I trace the histories of material "stuff" - metal ores, machinery, geological strata, mining waste, etc. - in relation to political economic concepts like class, value, resource, and property. I am intrigued by how historical meaning is sedimented within apparently inert materials, and how those histories continue to animate contemporary political economies. In this sense, cooperative miners are my guides not only to the underground but also to the histories that matter: their engagements and reflections reveal the degree to which colonial, scientific, and nationalist histories form the unseen foundations of political economic processes.

Beyond the macro-scale implications of this analysis, this project is fundamentally concerned with how race and gender articulate around the materialities, spaces, and practices of mining in highland Bolivia. It traces how corporeal differentiations are produced in and through uneven access to subterranean spaces, which in turn generates an uneven distribution of harms (chemical exposures, acidic water, silica dust) and benefits (profits). The region of Northern Potosí, where the tin mining towns of Llallagua and Uncía are located, is known for the strength of its ayllus (territorialized Quechua and Aymara communities) and a lot of the cooperative miners are active ayllu members and/or identify as originarios (original people). On the one hand, this defies widespread representations of cooperative miners, which are typically depicted as non-Indigenous precisely because of their involvement in resource extraction. On the other hand, racism remains within the cooperatives, where "newcomers" from the ayllus are usually relegated to the least productive zones of the mine. A similar process of bodily differentiation occurs along gendered lines, as most women work surface-level deposits with comparatively low ore content.

Below is a video of an interview I did in 2017 with Dave Koller from The Young Turks. At the time, Bolivian mining cooperatives were making international headlines because a group of them had just murdered Bolivia's vice minister of the interior, Rodolfo Illanes, at a protest. In the interview, I differentiate between types of mining cooperatives, explain their leadership structure, and offer some insights into why this particular protest became violent.

Selected publications from this project (see my CV for a complete list):

Marston, A. (In Press - 2024) Subterranean Matters: Cooperative Mining and Resource Nationalism in Plurinational Bolivia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Marston, A. (2023) Architectures of Extraction: Labor and Industrial Ruination in Highland Bolivia. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 1-20.

Marston, A. (2021) Of Flesh and Ore: Material Histories and Embodied Geologies. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111(7), 2078-2095.

Marston, A. (2020) Vertical Farming: Tin Mining and Agro-Mineros in Bolivia. Journal of Peasant Studies. 47(4), 820-840.

Marston, A. (2019) Strata of the State: Resource Nationalism and Vertical Territory in Bolivia. Political Geography. 74. DOI: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102040.

Marston, A. & Kennemore, A. (2019) Extraction, Revolution, Plurinationalism: Rethinking Extractivism from Bolivia. Latin American Perspectives 46(2), 141-160.

Marston, A. & Perreault, T. (2017) Consent, Coercion and Cooperativismo: Mining and Environmental Governance in Bolivia. Environment and Planning A 49(2), 252-272.

Marston, A. (In Press - 2024) Subterranean Matters: Cooperative Mining and Resource Nationalism in Plurinational Bolivia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Marston, A. (2023) Architectures of Extraction: Labor and Industrial Ruination in Highland Bolivia. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 1-20.

Marston, A. (2021) Of Flesh and Ore: Material Histories and Embodied Geologies. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111(7), 2078-2095.

Marston, A. (2020) Vertical Farming: Tin Mining and Agro-Mineros in Bolivia. Journal of Peasant Studies. 47(4), 820-840.

Marston, A. (2019) Strata of the State: Resource Nationalism and Vertical Territory in Bolivia. Political Geography. 74. DOI: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102040.

Marston, A. & Kennemore, A. (2019) Extraction, Revolution, Plurinationalism: Rethinking Extractivism from Bolivia. Latin American Perspectives 46(2), 141-160.

Marston, A. & Perreault, T. (2017) Consent, Coercion and Cooperativismo: Mining and Environmental Governance in Bolivia. Environment and Planning A 49(2), 252-272.